Economic health requires a healthy Environment and Society. It is past time that we start thinking that way and actually measure and talk about what a strong economy really means.

What does growth mean?

Growth is a common refrain in discussions and reporting about finance and economics. Growth takes many forms: Productivity growth. GDP growth. Jobs growth. Spending growth. Capital growth. Savings growth. Market growth. There is a long list of metrics related to tracking growth.

But what are we to make of growth? Should we focus so heavily on growth? And how much growth is enough?

Some aspects of growth are positive – it is hard to imagine that adding more jobs and employing more people is a bad thing. Or that it is problematic for families to increase their savings so they can pay unexpected bills and grow generational wealth. In those cases, growth adds value and benefits individuals. And improving the lives of individuals typically improves the health and resiliency of communities.

But many forms of growth aren’t inherently good. For example, productivity growth has substantial downsides as an indicator of economic and financial success despite a common belief that it is one of the best indicators for improving the standard of living.

How should it work?

In nature, constant growth is unsustainable, and all things tend toward an equilibrium. As the population of one species grows, their food supplies often decrease and the population of their predators grows, thereby slowing and ultimately reducing the growth of the species. This cycle repeats over and over, always returning to a more sustainable level of equilibrium.

And while there are expected or anticipated equilibriums in economics (e.g., unemployment), those aren’t a natural or inherent function of an economy and business leaders don’t manage their business to any equilibriums. Instead, their focus is to grow as large and as fast as possible. Sell more products. Expand to new markets. Increase productivity. We can infer that business leaders maintain a belief that growth is limitless and there are no repercussions.

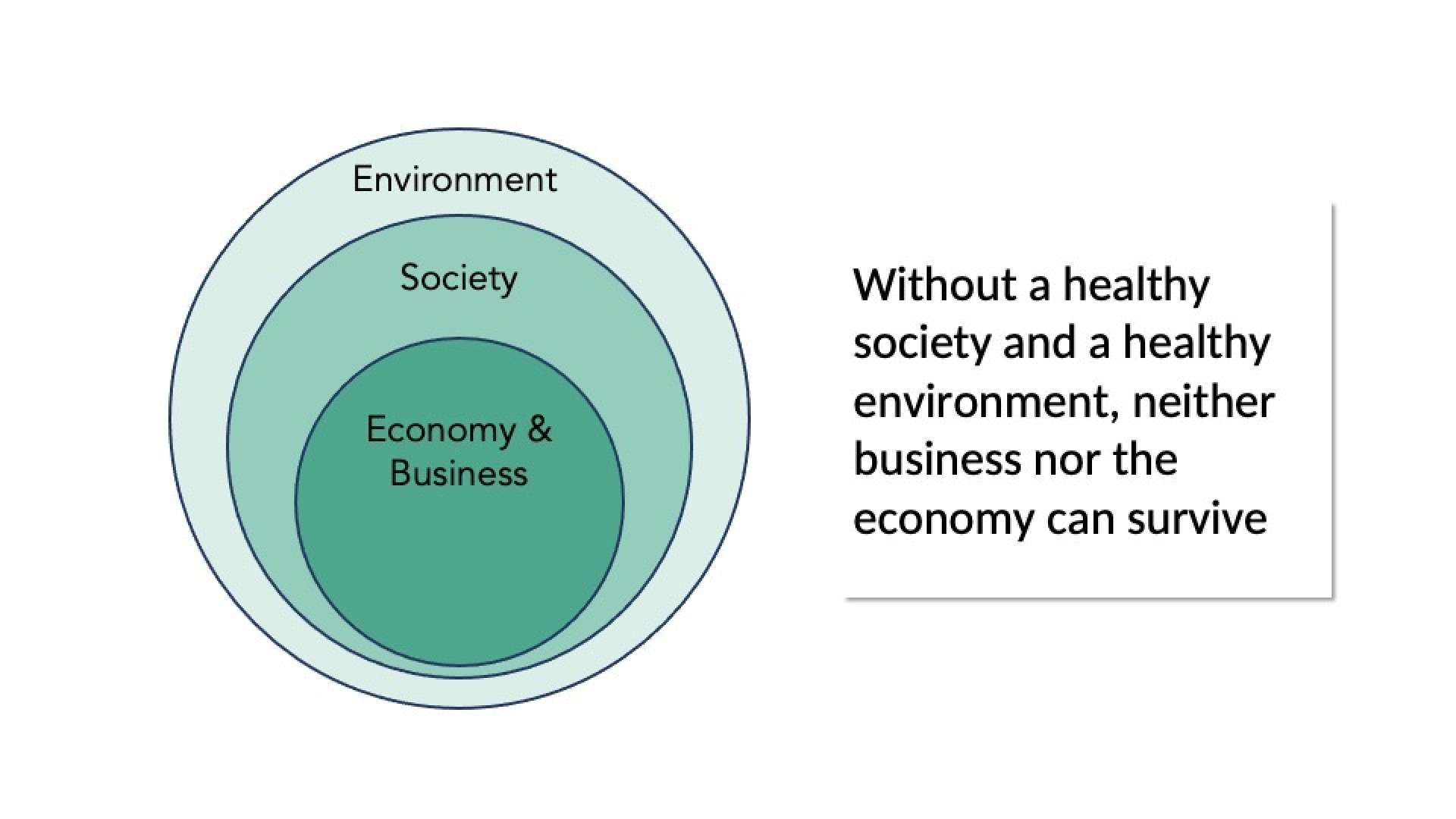

At Measure Meant, we subscribe to the nested economic model presented by Bob Doppett, Peter Senge, and others. This model is a departure from longstanding notions of the interaction between the economy, society, and the environment. Instead of society and the environment being resources for businesses to exploit, the nested model posits that the economy is dependent on society, which in turn is dependent on the environment. The relationship is symbiotic and is not compatible with unlimited growth.

In this economic view, we must understand that the environment is a fixed, finite resource that is not capable of growing. There is an upper bound that the natural environment can support.

With that in mind, unchecked societal growth can overwhelm the environment and thereby lead to the collapse of not just the environment, but society and the economy. Similarly, unbounded economic growth (as in its current form) can drive inequality that leads to wealth gaps, financial insecurity, homelessness, mental health issues, increased crime, and other social problems that can overwhelm the health of our society. That same economic growth can also overwhelm the environment through overuse, degradation, and elimination of natural resources and the entire ecosystem. In these scenarios, the environment, society, and the economy collapse. The economy doesn’t survive when Society and the Environment are not healthy.

Who benefits?

Our current, lived experience demonstrates the reality of this nested system and how thoughtless economic and societal growth is leading us towards a full system collapse. Companies produce an endless supply of low-quality products to meet an outsized and insatiable consumer demand. Low-quality products break or wear out quickly. Or a new model is introduced or new product created, and consumers quickly move on from the old version. The economy grows. The waste we produce grows. Landfills grow. And landfills tend to leak into waterways and emit methane, so pollution grows.

A company finds success and grows in their local market. Sales growth is high, so they grow the size of their stores to sell more. Local success isn’t enough, so they expand in the region to maintain growth. Regional growth stalls, so national expansion is next, possibly followed by global expansion. Founder’s and investor’s wealth grows.

Each step introduces the product to a broader set of consumers, who may get a new product that adds convenience or by getting a product at a lower cost. Large companies have greater buying power, allowing them to buy and sell at lower costs than competitors, particularly small local businesses. As the company grows in scale and revenue, there is a decline in small businesses because they can no longer compete.

This happened to butchers, bakers, milk trucks, and other small business in the 1960s with the advent and expansion of grocery stores. When consumers could get all their products in one location, they stopped frequenting local specialty stores and businesses because they were less convenient. Local sports stores have closed in favor of national chains (Dicks’s, Cabela’s). Locally owned car dealerships are replaced with large regional and national sellers (Carmax, AutoNation). Walmart’s expansion infamously drove small retailers out of business because they couldn’t compete on cost. Amazon is stifling local business by enabling consumers to buy anything they want from their couch.

This process creates economic oligopolies, or in some cases monopolies. Markets become less competitive as a few large companies gain significant market share. For those smaller companies that do remain, particularly as producers or suppliers, have few options and become subject to manipulation by larger firms.

What is happening?

Small farms are dwindling as meat, eggs, poultry, and dairy of large agri-firms begin to dominate these industries and consolidate into vertical operations: Just 4 companies are responsible for 80% of US beef production and 9 companies control 50% of the US egg market. Forbes reported in August 2022 that four companies control over 60% of the poultry industry. In 1978, the largest dairy farms held 1.3% of all farms and 10.8% of all cows. In 2017, that same 1.3% of farms had 31.7% of cows and the definition of “large” changed from farms with 200+ cows to farms with 2000+ cows.

Consumers benefit in some of these scenarios, either by paying less (in the short-term) for products they want or gaining convenience. But they lose more than they gain. Industry consolidation often reduces innovation because companies have less incentive to innovate to remain competitive. In some cases, consumers can lose choice because the only place to buy some products are big box stores which have limited selection. In most cases, consumers end up paying more.

The four companies that dominate meat packing are known as the Big Four (Tyson’s, JBS, Cargill, and National Beef). JBS, paid $2.3 billion in dividends in 2020, making it clear that the meatpackers are interested in one thing only: profit. And while JBS was paying record dividends, the average price per pound of ground beef climbed from $4.12 in 2020 to $4.79 in 2023, an increase of 16%.

The cost of raising cows isn’t contributing materially to the increased prices because farmers only receive about 14 cents of every dollar spent. And companies like JBS aren’t interested in supporting the farmers by a Tyson executive saying “that ‘because we run for margin and not market share, we’re not willing to overpay for cattle’.” They want to squeeze the farmer and others down the supply chain as much as possible.

The price increases are in large part due to market manipulation. As part of an antitrust filing against the Big Four, “[o]ne witness described a conversation with the head of fabrication of a JBS plant in Texas, in which he was told ‘that each [Big Four] Defendant expressly agreed to periodically reduce its purchase and slaughter volumes to reduce the prices they would pay for fed cattle.’” Another witness described the impact of that collusion, stating that the “packers ‘worked together to reduce their purchases of cash cattle’ because they realized that taking cattle out of the cash market would lower prices.” The companies don’t pass the savings from lower cattle prices to consumers, they keep it for themselves.

This focus on growth is hurting small business owners, employees, farmers, consumers, and society. It is a rigged game.

What, then?

Growth doesn’t measure the health of the economy. It measures increased demand and increased profit. Rather than focus so heavily on growth, we should be considering what enables that growth. People create the growth, both as employees and members of society.

We should consider workplace injuries and sick days as key indicators of economic stability along with employee satisfaction. We should consider the impacts to society in terms of the percent of employees making a family living wage, levels of poverty and homelessness, wealth inequality (e.g., GINI coefficient), hospitalization rates for chronic diseases and other ailments, and high school graduation rates amongst others.

We should also be measuring the health of the environment. Metrics might include PMI and air pollution levels at local, county, state, and national levels. Species extinction rates, water pollution indexes, soil health, the amount of undeveloped land and wildland habitats, and deforestation rates might be a place to start.